|

On April 4, 2000, George Cameron Finlay and I took of from Schwäbisch

Hall in the south of Germany to ferry N267LM to Waterloo, Iowa for its

owners. N267LM is a pressurized Cessna P210N Centurion. |

All pictures can be clicked to see enlargements

George has quite a bit of experience ferrying planes across the Atlantic.

For me it was the first time. Seven-Lima-Mike is also the largest plane

I have flown to date.

George has quite a bit of experience ferrying planes across the Atlantic.

For me it was the first time. Seven-Lima-Mike is also the largest plane

I have flown to date.

7LM already had its ferry tank installed when we arrived. It was a cube-shaped

100-gallon tank made of aluminium, strapped to the floor of the cabin behind

the pilots. Two passenger seats had been removed to make place for it.

The tank was plumbed into the fuel line from the right wing tank. While

flying on the left tank, we could refill the right, using cabin pressure

to push fuel up into the wing tank.

We spent the afternoon of Monday April 3 to preflight the plane, fill

the tanks, check for leaks and get everything ready for departure at dawn

the next day.

First leg, EDTY (Schwäbisch Hall-Hessental) - EGPC (Wick)

Clearance: Cessna N267LM is cleared to BIRK (Reykjavik). Direct DKB, G5

to FUL, B5 to HMM, SPY, OTR, NEW, TLA, GOW, BEN, Direct 59:00N10:00W, M027,

BIRK, flight level 180.

Flight time: 4.5 hrs, IMC: 1hr

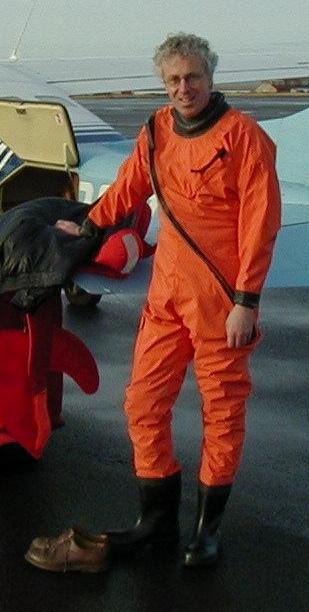

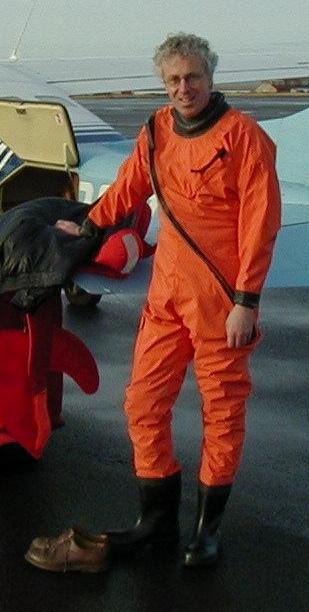

We donned our suits (I rented one from De

Wolf Products in Yerseke -- thanks guys, for excellent service!) and

fired up the engine at seven, the time the airport opened, and taxied from

EDTX (Schwäbisch Hall-Weckrieden) across the road to EDTY (Schwäbisch

Hall-Hessental). To do this, we had to cross a two-lane county road. EDTY

is in Class Foxtrot airspace, something we are not familiar with in the

US. We believe it means the airport is essentially uncontrolled but that

it does provide IFR air traffic advisories and clearances. (In Canada, Class F

is a form of restricted airspace, apparently, but Germany is ICAO land).

We donned our suits (I rented one from De

Wolf Products in Yerseke -- thanks guys, for excellent service!) and

fired up the engine at seven, the time the airport opened, and taxied from

EDTX (Schwäbisch Hall-Weckrieden) across the road to EDTY (Schwäbisch

Hall-Hessental). To do this, we had to cross a two-lane county road. EDTY

is in Class Foxtrot airspace, something we are not familiar with in the

US. We believe it means the airport is essentially uncontrolled but that

it does provide IFR air traffic advisories and clearances. (In Canada, Class F

is a form of restricted airspace, apparently, but Germany is ICAO land).

George flew on the first day, I operated the radio and did the navigation.

Our departing runway was 26, a 920 meter (3000 ft) runway which, given

our maximum gross weight, required a short-field take-off. After take off,

we discovered that the yellow gear-up light wasn't working.

George flew on the first day, I operated the radio and did the navigation.

Our departing runway was 26, a 920 meter (3000 ft) runway which, given

our maximum gross weight, required a short-field take-off. After take off,

we discovered that the yellow gear-up light wasn't working.

We were immediately cleared to our cruising altitude of 18,000 feet and

had good ground contact initially, but a gradually thickening cloud layer

below soon hid the ground so I didn't get to see my home town Amsterdam.

We were immediately cleared to our cruising altitude of 18,000 feet and

had good ground contact initially, but a gradually thickening cloud layer

below soon hid the ground so I didn't get to see my home town Amsterdam.

The engine ran somewhat hot when we leaned it according to the book (both

EGT and CHT). Our airspeed was a bit higher than book speed, however, and

there was a sign on the tachometer `zeigt 100 umdrehungen zo wenig an',

so we reduced the RPM to 2400 on the dial and leaned for 2500. This worked

well during the rest of the trip as the picture shows.

The engine ran somewhat hot when we leaned it according to the book (both

EGT and CHT). Our airspeed was a bit higher than book speed, however, and

there was a sign on the tachometer `zeigt 100 umdrehungen zo wenig an',

so we reduced the RPM to 2400 on the dial and leaned for 2500. This worked

well during the rest of the trip as the picture shows.

We filled the right wing tank from the ferry tank for the first time.

It appeared to work well, but the tank made funny clunking noises.

The headwinds became stronger over the North Sea and were forecast to increase

further. We decided to land in Wick, Scotland, and visit Andrew Bruce,

George's buddy at

Far

North Aviation.

The headwinds became stronger over the North Sea and were forecast to increase

further. We decided to land in Wick, Scotland, and visit Andrew Bruce,

George's buddy at

Far

North Aviation.

When we lowered the gear, we did not get a green light. Since the gear-up

light was already broken, swapping bulbs didn't help. We tried pumping

down the gear and immediately met with the resistence consistent with the

gear being down already. We also knew that the gear horn was working, so

we were not very concerned. Nevertheless, we decided to do a low pass over

the runway to have the controller confirm our nosewheel down.

When we lowered the gear, we did not get a green light. Since the gear-up

light was already broken, swapping bulbs didn't help. We tried pumping

down the gear and immediately met with the resistence consistent with the

gear being down already. We also knew that the gear horn was working, so

we were not very concerned. Nevertheless, we decided to do a low pass over

the runway to have the controller confirm our nosewheel down.

After the fly by, we made a circuit around the pattern and landed uneventfully

on a very breezy and cold Wick. Spring had not arrived here.

After the fly by, we made a circuit around the pattern and landed uneventfully

on a very breezy and cold Wick. Spring had not arrived here.

Andrew immediately pored over our ferry tank and diagnosed a blocked

vent tube. This explained the tank's clunking noises. Andrew replaced the

fuel cap on the ferry tank and the tank remained silent for the rest of

the trip. He also fixed our landing gear light.

With tanks once more filled to the brim and our stomachs too, we departed

on our second leg.

Second leg, EGPC (Wick) - BIRK (Reykjavik)

Clearance: Cessna N267LM is cleared to BIRK. Direct 61:00N10:00W, Direct

Aldan, EL, BIRK, flight level 180.

Flight time: 4hrs, IMC: 0.5 hrs

Departure and climb out were uneventful and we soon settled to monitoring

the instruments and our three GPSs. We had two hand-held GPSs and an IFR

approved panel-one.

Departure and climb out were uneventful and we soon settled to monitoring

the instruments and our three GPSs. We had two hand-held GPSs and an IFR

approved panel-one.

On previous trips, at lower altitudes, George always had to ask aircraft

overhead to relay his position. This time, we remained in direct radio

contact for the whole leg. But we soon lost our navigation by radio beacons.

We caught some glimpses of the North Atlantic below us, but for the

most part we had a solid undercast. We were wearing our survival suits

up to our middle, and the two-person raft and satellite beacon were at

my feet. The statistics show that the survival rate for ditchings, even

in the middle of the Atlantic, is surprisingly good, provided the crew

manages to prevent hypothermia by wearing survival suits. But, flying

over the Atlantic Ocean, three hours from the nearest land, does not make

you feel any too comfortable.

The engine purred happily however, and we were soon past the halfway point.

We started talking to Iceland Radio who amended our clearance, essentially

by adding extra waypoints to our existing clearance. George offered me

the approach from the right seat, but I had to give it back to him -- I

had never done an approach from the right seat and I hadn't flown a P210

before; I just couldn't get the appraoch stabilized.

The engine purred happily however, and we were soon past the halfway point.

We started talking to Iceland Radio who amended our clearance, essentially

by adding extra waypoints to our existing clearance. George offered me

the approach from the right seat, but I had to give it back to him -- I

had never done an approach from the right seat and I hadn't flown a P210

before; I just couldn't get the appraoch stabilized.

George (the real one, not the autopilot) led us down through the clouds

on the

ILS into Runway 20 at

Reykjavik.

We broke out roughly at a thousand feet and landed in a mild breeze.

George (the real one, not the autopilot) led us down through the clouds

on the

ILS into Runway 20 at

Reykjavik.

We broke out roughly at a thousand feet and landed in a mild breeze.

The hotel was immediately behind the FBO and we were checked in by 6:30

local time. We had dinner at a fish restaurant that was recommended to

us, called

Thrír

Frakkar. The white brigade is led by a father-and-son team, while mother

and daughter preside over the comfort of the guests. The food was both

original and excellent and the service both quick and friendly.

Third leg, BIRK (Reykjavik) - BGSF (Søndre Strømfjord)

Clearance: Cessna N267LM is cleared to BGSF, via 65:10N-25:00W, 65:30N-30:00W,

65:35N-34:54W, BGKK, Masir, Pevar, flight level 180.

Flight time: 5 hrs, IMC: 0.5 hrs

After climbing into our suits, we set of to Greenland. We changed seats

on the second day of our trip and George operated radios and did our navigation.

We had grown accustomed to flight level 180 and so we filed for it and

got it on this leg as well.

After climbing into our suits, we set of to Greenland. We changed seats

on the second day of our trip and George operated radios and did our navigation.

We had grown accustomed to flight level 180 and so we filed for it and

got it on this leg as well.

Reykjavik was almost sunny when we left it around 8 am and over most of

Greenland we had a magificent view of the snow and ice below. we flew directly

over Kulusuk (BGKK), which looked very forlorn deep below us. Later, in

Søndre Strømfjord, I asked the man who helped us at the FBO

what it was like to live there. He told us that nowadays, people live there

with their families and that Søndre Strømfjord has a permanant

population of 400 or so, 18 children among them. George and I decided that

this was not for us, although George did look longingly at the Ice-Patrol

aircraft parked at the airport.

Reykjavik was almost sunny when we left it around 8 am and over most of

Greenland we had a magificent view of the snow and ice below. we flew directly

over Kulusuk (BGKK), which looked very forlorn deep below us. Later, in

Søndre Strømfjord, I asked the man who helped us at the FBO

what it was like to live there. He told us that nowadays, people live there

with their families and that Søndre Strømfjord has a permanant

population of 400 or so, 18 children among them. George and I decided that

this was not for us, although George did look longingly at the Ice-Patrol

aircraft parked at the airport.

As we approached BGSF and reported the airport in sight we nevertheless

declined a visual approach to runway 10 because of clouds over the fjords.

We took the

LOC/DME approach and brushed those

clouds lightly on the way down. The last 8 to 10 miles of the descent were,

however, in the clear and in wonderful sunshine. Winds were calm; just

the way I like them for my first approach in an unfamiliar aircraft.

As we approached BGSF and reported the airport in sight we nevertheless

declined a visual approach to runway 10 because of clouds over the fjords.

We took the

LOC/DME approach and brushed those

clouds lightly on the way down. The last 8 to 10 miles of the descent were,

however, in the clear and in wonderful sunshine. Winds were calm; just

the way I like them for my first approach in an unfamiliar aircraft.

After parking, the marshals chocked our plane and told us there was no

fuel. That got our attention, but then they went on

to say that it was only because a Scandinavian Airlines Boeing 767 was

parked on top of the fuel outlet. It would leave in an hour and then

there'd be fuel again. That was a relief.

After parking, the marshals chocked our plane and told us there was no

fuel. That got our attention, but then they went on

to say that it was only because a Scandinavian Airlines Boeing 767 was

parked on top of the fuel outlet. It would leave in an hour and then

there'd be fuel again. That was a relief.

We went off in search of a weather briefing, a flight plan form and lunch.

We had lunch in the combination airport lounge/airport hotel. Here we discovered

that Søndre Strømfjord cannot possibly be famous for its

cuisine and that it is nevertheless a popular tourist destination. We did

not see what the attraction of coming to this handful of houses in the

middle of nowhere could be, but Scandinavian Airways obviously flies 767s

there and one assumes they make a profit.

We went off in search of a weather briefing, a flight plan form and lunch.

We had lunch in the combination airport lounge/airport hotel. Here we discovered

that Søndre Strømfjord cannot possibly be famous for its

cuisine and that it is nevertheless a popular tourist destination. We did

not see what the attraction of coming to this handful of houses in the

middle of nowhere could be, but Scandinavian Airways obviously flies 767s

there and one assumes they make a profit.

When the 767 left, the marshals guided us to the pumps and we had all

the tanks filled for a relatively short hop to Frobisher Bay (Iqaluit).

We didn't really want to land there but customs insisted.

When the 767 left, the marshals guided us to the pumps and we had all

the tanks filled for a relatively short hop to Frobisher Bay (Iqaluit).

We didn't really want to land there but customs insisted.

Fourth leg, BGSF (Søndre Strømfjord) - CYFB (Iqaluit)

Flight time: 3 hrs, IMC: 0.5 hrs

After takeoff, we flew out over the Fjord and looked down at the snowscape.

Later, we looked at the ice floes and the occasional iceberg among them.

We mistook one for a ship and imagined ourselves ditching next to it should

the engine fail. Good thing it didn't.

After takeoff, we flew out over the Fjord and looked down at the snowscape.

Later, we looked at the ice floes and the occasional iceberg among them.

We mistook one for a ship and imagined ourselves ditching next to it should

the engine fail. Good thing it didn't.

The flight to Iqaluit is relatively short, the weather was perfect and

we made a visual approach to Runway 18. Customs formalities took just moments

so we topped off the tanks and were soon off again to the south.

The flight to Iqaluit is relatively short, the weather was perfect and

we made a visual approach to Runway 18. Customs formalities took just moments

so we topped off the tanks and were soon off again to the south.

Fifth leg, CYFB (Iqaluit) - CYGL (La Grande Riviere)

Clearance: Cessna N267LM is cleared to CYGL. Direct YLC, YKG, YPX, YPH,

YMU, YGW, CYGL, flight level 180.

Flight time: 4 hrs, IMC: 1hr

We picked La Grande Riviere as our final destination for the day. Its pretty

name and its location en route to Waterloo, Iowa made it the ideal destination

for the day.

We picked La Grande Riviere as our final destination for the day. Its pretty

name and its location en route to Waterloo, Iowa made it the ideal destination

for the day.

Our clearance took us on a series of hops from one NDB to the next.

We really got to fly those NDBs because two out of three GPSs refused to

see a sufficient number of satellites while the third suffered from a European

rather than an American database. Good excercise.

Our position reports did not appear to be heard by anyone, so we called

on planes overhead to relay them for us. The second time we did this, we

managed to get a controller again -- at Umiujaq or Kuujjuarapik,

I forgot to write it down -- who relayed not only our position, but also

our request for hotel rooms in La Grande Riviere.

When we arrived after a flight that seemed to take for ever, it was

dark. It was also bitterly cold. A friendly refueller filled our tanks

and then drove us to the hotel which was in town, a thirty-minute drive

over partially icy roads at speeds around 100 km/h. When we got to the

hotel -- around ten pm -- all restaurants had closed (if there were as

many as two). We went to the bar where, it was suggested, we could order

eggs and sausages. Sounded good.

Both eggs and sausages turned out to be pickled and virtually inedible.

We managed to wash them down with beer and peanuts and went to bed.

Sixth leg, CYLG (La Grande Riviere) - KMSP (Minneapolis St Paul)

Clearance: N267LM is cleared to KMSP, via AR18 ZEM, AR20 YMO, V6 YAN, V7

YGQ, V13 YQT, Wagnr, direct; 16,000 feet

Flight time: 5.4 hrs, IMC 0 hrs.

We had to go though customs in the USA, so we needed one stop before Waterloo,

Iowa (KALO, by the way). George first planned on going to DesMoines, Iowa,

but a big low with lots of wind and tops well in the flight levels was

in our way. Instead, we went to Minneapolis St Paul, around the low, with

a good chance of some tailwinds (which, of course, we didn't get).

George got back in the left seat on day three. It was very cold still and

the engine didn't start right away. But we did get it going without outside

help and we gently let it get a bit warmer before take off. On climb out,

we punched through a low thin layer of clouds to our cruising altitude

of 16,000 feet.

George got back in the left seat on day three. It was very cold still and

the engine didn't start right away. But we did get it going without outside

help and we gently let it get a bit warmer before take off. On climb out,

we punched through a low thin layer of clouds to our cruising altitude

of 16,000 feet.

On the way to MSP we were in and out of very thin clouds or very thick

haze that, for the most part, allowed us to see ground as well as sun,

but no horizon. After passing Duluth, we were let down to 5000 feet where

we met with the first (very light) turbulance of the trip; We were cleared

for a visual approach to runway 30R at MSP, flying to it on a long base

leg from the northeast to a half-mile final.

We asked and got progressive taxi to customs. After clearing customs,

George set off on his last leg to Waterloo by himself, while I caught a

commercial flight back home.

Total flight time form EDTX to KMSP was 25.9 hours, of which 3.5 hours

in instrument conditions. Total (flight-plan) distance was 4327 nautical

miles (great-circle distance from EDTX to KMSP is 3882 miles). Average

ground speed 167 knots. TAS at 18000 feet was close to 180 kts.

We had a light tailwind until the North Sea and light headwinds (or a headwind

component) pretty much all of the remainder of the trip. We made six landings.

We could have flown every leg without using the ferry tank (but that is

not to be taken as encouragement to try this without one).

Post Scriptum -- Taking a Sea Survival Course

Inspired by the transatlantic trip, George signed us up for a sea survival

course given by

Survival

Systems, Inc. in Groton, CT (KGON). The course was given for just the

three of us: George Finlay, Ken Thompson and myself.

We flew there from Morristown Muni, NJ (KMMU) in one of the club's 172s.

Naturally, when there are two CFIIs on board, the non-instructor (i.e., me) gets put

in the left seat, hooded and heckled all the way.

The course started with an hour or so of theory and reviewing survival

equipment. The emphasis was, of course, on survival in very cold water.

We learned that in a good survival suit your body temperature will go down

no more than 2°C after 6 hours in water of 2°C. We then tried on

three different suits.

The three suits all had hoods and attached boots. One had integrated

gloves. All suits also were well insulated, two of them by a removable

liner on the inside. The hoods have a seal that leaves only the face exposed.

They are quite uncomfortable under the chin. The suit I wore during flight

has a neck seal and leaves the head free. Having worn both styles, I think

the neck seal is better, because it can actually be worn during flight.

The hooded suits are just too uncomfortable. Our instructor demonstrated

a separate hood, much like divers wear.

We tried the suits in the pool and had a great time practising getting

into and out of the raft, turning the raft right-side up, being hoisted

out of the water in a basket or a horse collar and climbing a rope net.

Then we had lunch and after lunch we went out to sea.

We were all apprehensive about this. The water of the Long Island Sound

is only 5°C in April and there was a strong wind. We set out in a fast

boat and got to try out some flares and smoke signals before we were dumped

overboard. We were assigned positions along the 60-yard lanyard of the

raft and went overboard.

The surprise of the day was that it was not in the least cold to be

in the ocean wearing a good survival suit. We splashed around very comfortably.

George started pulling the lanyard out of the raft and Ken and I stayed

at the end of the line. When George had collected the remaining 50 yards,

he gave a tug and the raft inflated -- right side up. He started climbing

into the raft and let go of his 50 yards of lanyard. Immediately, the wind

carried the raft away from Ken and me and we had to haul in those 60 yards

to get back to the raft.

We all climbed in and were joined by the instructor who proceeded to

explain how seasick his clients always became. In fact, he positively

bragged that he had never had a group without someone getting sick. He

then managed a vivid description

of the smell of vomit sloshing around in the bottom of the raft and didn't

stop before one of us had to put his head over the side.

After that, we were allowed to climb out on top of the tent and felt

much better.

The instructor explained the survival gear on board: knife, water desalination

kit, seasickness pills, rations, etc. He stretched the explanation to an

hour or so, presumably to make us realise that survival at sea isn't fun.

I don't think any of us believed that anyway.

All in all, the course was very useful and has given me a much better

idea what to look for in survival equipment and how to prepare for long

overwater trips.

For more information, you have to look at Doug Ritters survival

page Equipped to Survive. It has

loads and loads of excellent information.

We donned our suits (I rented one from De

Wolf Products in Yerseke -- thanks guys, for excellent service!) and

fired up the engine at seven, the time the airport opened, and taxied from

EDTX (Schwäbisch Hall-Weckrieden) across the road to EDTY (Schwäbisch

Hall-Hessental). To do this, we had to cross a two-lane county road. EDTY

is in Class Foxtrot airspace, something we are not familiar with in the

US. We believe it means the airport is essentially uncontrolled but that

it does provide IFR air traffic advisories and clearances. (In Canada, Class F

is a form of restricted airspace, apparently, but Germany is ICAO land).

We donned our suits (I rented one from De

Wolf Products in Yerseke -- thanks guys, for excellent service!) and

fired up the engine at seven, the time the airport opened, and taxied from

EDTX (Schwäbisch Hall-Weckrieden) across the road to EDTY (Schwäbisch

Hall-Hessental). To do this, we had to cross a two-lane county road. EDTY

is in Class Foxtrot airspace, something we are not familiar with in the

US. We believe it means the airport is essentially uncontrolled but that

it does provide IFR air traffic advisories and clearances. (In Canada, Class F

is a form of restricted airspace, apparently, but Germany is ICAO land).

Departure and climb out were uneventful and we soon settled to monitoring

the instruments and our three GPSs. We had two hand-held GPSs and an IFR

approved panel-one.

Departure and climb out were uneventful and we soon settled to monitoring

the instruments and our three GPSs. We had two hand-held GPSs and an IFR

approved panel-one.

After takeoff, we flew out over the Fjord and looked down at the snowscape.

Later, we looked at the ice floes and the occasional iceberg among them.

We mistook one for a ship and imagined ourselves ditching next to it should

the engine fail. Good thing it didn't.

After takeoff, we flew out over the Fjord and looked down at the snowscape.

Later, we looked at the ice floes and the occasional iceberg among them.

We mistook one for a ship and imagined ourselves ditching next to it should

the engine fail. Good thing it didn't.