Flying around Manhattan

Flying around Manhattan is one of the prettiest and spectacular

things you can do with a small airplane in the north east of the US.

We’re based in Morristown, NJ, a mere stone’s throw from the city

so I end up doing it quite often. Below is a report of a recent

trip I made (my seventy-first). I’m hoping it’ll provide

some insight to pilots who’d like to do it for the first time.

I

like to do these Hudson trips at night, for a couple of reasons.

My passengers are often first-time fliers in small planes, so the

lack of turbulence at night makes for a more comfortable flight for

them. Second, the night view of Manhattan is absolutely

spectacular, much more so than during the day. Third, and this

is my most important reason, there is very little traffic over the

Hudson at night and, what traffic there is, is very visible.

The Hudson is crowded with planes and helicopters during the day, but

there are few at night.

I

like to do these Hudson trips at night, for a couple of reasons.

My passengers are often first-time fliers in small planes, so the

lack of turbulence at night makes for a more comfortable flight for

them. Second, the night view of Manhattan is absolutely

spectacular, much more so than during the day. Third, and this

is my most important reason, there is very little traffic over the

Hudson at night and, what traffic there is, is very visible.

The Hudson is crowded with planes and helicopters during the day, but

there are few at night.

We flew on a Friday evening, in August; the Yankees were playing

the A’s at home and the stadium TFR wouldn’t allow us nearer than

three miles from Yankee Stadium. A three mile circle just

covers the Hudson, so the area a mile or two north and south of the

George Washington Bridge becomes a no-fly zone (check yankees.com

before you go and, need I tell you always to

check the NOTAMs?). There is a

three-mile circle around Shea Stadium (New York Mets) also, but it is

wholly included in the Class B section that goes to the surface

around La Guardia.

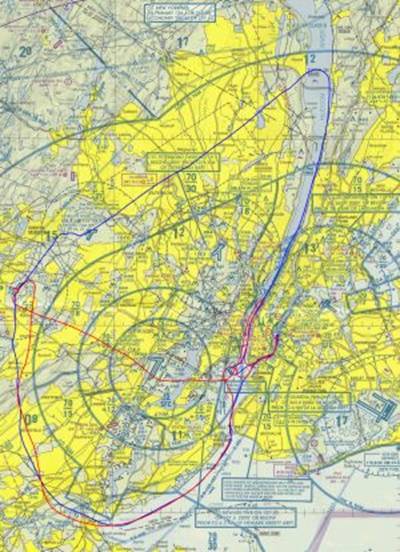

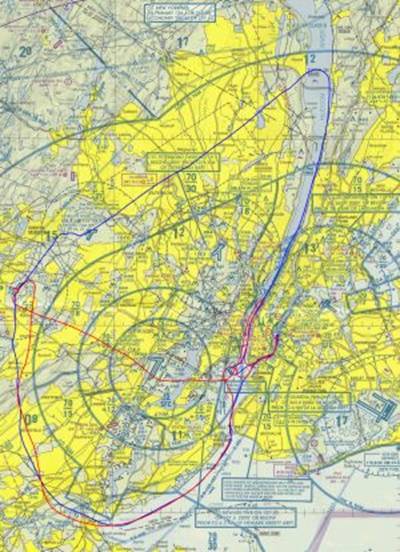

My normal route of flight would be to return to Morristown by

heading north on the Hudson to the Tappan-Zee bridge and then turn

hard left, following the 244° radial from Carmel VOR direct to

Caldwell continuing direct to Morristown (see the dark blue track on

the map). From the G-W bridge on that allows me to give the

passengers an opportunity to hold the controls. We’d slowly

climb from 1000 feet over the G-W Bridge to 1800 feet – an altitude

that allows approaches into Teterboro to come in over our heads.

But, as I mentioned, that option was out. We flew the track

marked in red on the map below (click on it for a larger version).

We took off from MMU runway 5 at a few minutes after 10 pm, made a

right turn-out to the south and skirted the Class Bravo 1500 foot

boundary on the outside. We looked down at Bell Labs, Murray

Hill, and my house in North Plainfield (couldn’t find the latter in

the clutter, of course) and then proceeded to the Raritan River, a

good landmark at night. There we gently turned left, crossing

the Garden State Parkway on the south shore of the Raritan.

This avoids the appendix on the 1500-foot Class Bravo for Newark’s

Runways 4 (see map, southernmost point of both tracks).

Then it was north-east along the Staten Island coast, while

descending below 1500 feet and then down to 1000 feet to cross the

Verrazano Narrows Bridge. This is a good time to make sure you

have your taxi or landing light on.

I

always start self-announcing on 123.05 just before the bridge.

I usually say something like

I

always start self-announcing on 123.05 just before the bridge.

I usually say something like

“Hudson Traffic, Skylane, one mile from the Verrazano

Bridge, Northbound, One Thousand.”

We then crossed over to “The Lady” and circled it clockwise

(passengers are on the right, mostly). Make sure you announce

doing this – every helicopter in the area does it too. The

helicopters usually do it at 500 feet or so. I always stay at

800 feet or higher, for a little extra assurance. When another

aircraft self-announces, by the way, and it’s close, it is a polite

and useful thing to announce your own position and to tell them you

have them in sight.

After the Lady, we swung around Governor’s Island into the East

River. The East River has its own self-announce frequency of

123.075. Do I have to tell you to get an

up-to-date VFR Terminal Map for New York?

At the north end of Roosevelt Island, the East River dead-ends

onto LGA’s air space. I always turn around well south of the

Island, where the river is nice and wide. I warn the passengers

of the G-forces and usually make a 60°-banked turn (it’s my

sadistic streak – 45° is plenty to make the turn – but do

brief your passengers on the turn or they’ll freak out).

Watch the wind – it’s usually from the west, so a left turn is

into the wind. Rarely, winds are from the east, however, and

then a right turn makes more sense to keep the radius small.

Remember, the turn takes 20 to 30 seconds and a 10 knot wind will

displace you by 300 to 450 feet during that turn; that’s

significant. Also, slow down before turning. The radius

of the turn dramatically increases with speed. Make sure you

announce well and look behind you before turning. Do I need to

tell you to be proficient in steep turns

before venturing into the East River? This is not a place to

practice them.

If you want to learn a bit more about making

optimal steep turns, look here.

We then crossed the three BMW bridges again in reverse order

(Williamsburg, Manhattan, Brooklyn), rounded Battery Park and flew

north on the Hudson. I usually announce the Holland Tunnel, the

Intrepid (aircraft carrier), the Reservoir in Central Park and the

G-W Bridge. This time we only went as far north as the middle

of Central Park. Turning around over the Hudson is easier than

over the East River: it’s wider.

When we got close to the Lady again, I called Newark Tower on

127.85 and asked to cut through the Class Bravo to MMU:

“Newark Tower, Skylane Four Seven Five Seven Tango.”

“Airplane calling, go ahead”.

“Skylane Four Seven Five Seven Tango is near The Lady, one

thousand feet, landing Morristown, request fly over Newark Airport to

Morristown.”

“Skylane Four Seven Five Seven Tango, Newark Tower, you are

cleared into the Class Bravo airspace, climb and maintain one

thousand five hundred feet, fly directly over the Runway 04 numbers,

then direct Morristown, squawk 4321.”

“Cleared direct numbers Runway Four, direct Morristown, one

thousand five hundred, Skylane Four Seven Five Seven Tango.”

“Skylane Five Seven Tango, Newark Tower, radar contact, one

thousand three hundred … make that one thousand four hundred,

Newark altimeter two niner niner eight.”

“Two niner niner eight, Five Seven Tango.”

Before calling, make sure you can find either the Rwy 4 or the Rwy

22 numbers because they’ll make you fly over them every time.

There’s a lot of ground clutter and it’s hard to spot Newark

airport from the Statue. A GPS helps a lot, of course.

Otherwise, look for I-78 which runs west to east towards the Statue,

directly north of the airport (see map again). Newark

controllers are often pretty busy, so don’t expect to get that

clearance over EWR every time; just be prepared to fly the long way

back.

When we got Morristown in sight, we were still at 1500 feet in

Class Bravo airspace:

“Newark Tower, Skylane four seven five seven tango has

Morristown airport in sight.”

“Skylane five seven tango, frequency change approved, keep the

squawk”

“Five seven tango, roger, thank you and good night.”

By this time (a few minutes after 11), Morristown Tower had

closed. We self announced (scanned the final approaches of

Runways 5 and 23 carefully for corporate jets with tired pilots

arriving late) and landed Rwy 5 (I don’t like straight in to Rwy 31

when the tower is closed – you can’t see what’s happening on

the other runway).

On rare occasions, you get really lucky. Returning one day

from a day trip to Block Island, I had flight following along the

coast of Connecticut and I was cleared into the Class Bravo (without

asking). I told the controller I wanted to fly to the Hudson

and fly the VFR corridor south and the controller then cleared me

over the Throg’s Neck Bridge, the tower cab of La Guardia and

Central Park at 2000 feet, followed by a left turn onto the Hudson

River. One of my passengers took these photos. It gave us

a uniquely new perspective on the city from a slightly higher

altitude than normal – and without sight-seeing helicopters to

worry about. Each of the pictures can be clicked for a large

version.

September 2006, Sape Mullender

Post Scriptum

After the Cory Lidle crash into a Manhattan building, the FAA

issued a NOTAM for the East River:

6/3495

(#3) ZNY EFFECTIVE

IMMEDIATELY UNTIL FURTHER NOTICE, VFR FLIGHT OPERATIONS INVOLVING

FIXED WING AIRCRAFT (EXCLUDING AMPHIBIOUS FIXED WING AIRCRAFT LANDING

OR DEPARTING NEW YORK SKYPORTS INC SEAPLANE BASE) IN THE EAST RIVER

CLASS B EXCLUSION AREA EXTENDING FROM THE SOUTHWESTERN TIP OF

GOVERNORS ISLAND TO THE NORTH TIP OF ROOSEVELT ISLAND, ARE PROHIBITED

UNLESS AUTHORIZED AND BEING CONTROLLED BY ATC. TO OBTAIN

AUTHORIZATION CONTACT LGA ATCT SOUTH OF GOVERNORS ISLAND ON 126.05.

(Have you ever wondered by the FAA speaks to us mostly in

CAPITALS?

– But I digress.) I felt that was the end of my East-River

excursions. On a recent flight around the city, however, I

decided to consult the authorities directly: I called La Guardia

Tower (by phone, while on the ground) and asked what their policy was

regarding flying the East River. The controller was very

friendly and told me that, if at all possible, they will grant access

to fixed-wing planes, usually in the Class Bravo just above the

East-River exclusion zone. That sounded like great news, so I

climbed into one of our planes and took off for a new excursion

around Manhattan (with a Columbia University professor as my

passenger).

I took the usual route to the Verrazano Bridge and, half way

between it and Governor’s Island, called La Guardia Tower on

126.05:

“La Guardia Tower, Skyhawk 738SQ, East-River request”.

“Aircraft calling, go ahead”.

“La Guardia, Skyhawk 738SQ is 2 miles south of Governor’s

Island, one thousand; request flying into the East River, with a

one-eighty south of Roosevelt Island”.

The controller cleared me into the Class Bravo, told me to climb

to 1500 feet and gave me a squawk code. He approved my plan and

I acknowledged.

He then asked me if, instead, I wanted to fly all the way to the

northern tip of Roosevelt Island and cross Central Park to the

Hudson. That sounded pretty good, so that’s what we did.

It’s a gorgeous way to see the city.

After crossing the park, we stayed with La Guardia Tower until we

had crossed the George Washington Bridge (the G.W., as it’s called

by pilots) where he told us to continue north and squawk VFR.

Lately, I’ve called LGA tower soon after crossing the Verazzano

bridge northbound. I request a clockwise 360 around the

southern half of Manhattan: Hudson, Central Park, East River, Battery

Park, Hudson north to the Tappan Zee Bridge. I have always

received permission. You get a squawk code and you’re asked

to climb to 1500 feet.

June 2007/April 2008, Sape Mullender

Post Post Scriptum

Recently, a Piper Saratoga

and a Eurocopter collided and crashed into the Hudson, killing 9.

This was the first mid-air collision in the Hudson exclusion zone.

Although we should always seek ways to improve flight safety in the

exclusion zone, just closing it to general-aviation traffic, as 15

members of congress seem to want, is an overreaction (I put a copy of

the letter here).

In

a letter to the FAA administrator, they say

“The

Hudson River flight corridor presents unique challenges, but the

danger of unregulated on-demand aircraft is also a widespread problem

in the New York region and the country. According to the DOT IG,

there were 33 accidents and 109 fatalities involving on-demand

aircraft in 2007 and 2008. And these types of collisions have been

happening for decades.”

nicely

suggesting that the bottom of the Hudson is littered with aircraft

wrecks. In fact, the DOT added two footnotes in their report to these

two sentences:

In

2007 and 2008, commercial air carriers had zero passenger deaths

although they flew significantly more hours than on-demand

operators.⁵ In contrast, during that same period, there were 33

fatal on-demand accidents, resulting in 109 deaths.⁶

⁵ Commercial

air carriers flew five times more flight hours in 2007 than on-demand

operators.

⁶

This

is the total for all on-demand operators, including air ambulance and

cargo.

It

would be great if flight-following were made available for Hudson

tours at all altitudes (it already is, on a voluntary basis and

requires flying above 1000 feet), but I fear that, in a typical

overreaction, the Hudson might be closed to general-aviation traffic

and the most beautiful flight one can make in the northeast will no

longer be possible.

August,

2009, Sape Mullender

I

like to do these Hudson trips at night, for a couple of reasons.

My passengers are often first-time fliers in small planes, so the

lack of turbulence at night makes for a more comfortable flight for

them. Second, the night view of Manhattan is absolutely

spectacular, much more so than during the day. Third, and this

is my most important reason, there is very little traffic over the

Hudson at night and, what traffic there is, is very visible.

The Hudson is crowded with planes and helicopters during the day, but

there are few at night.

I

like to do these Hudson trips at night, for a couple of reasons.

My passengers are often first-time fliers in small planes, so the

lack of turbulence at night makes for a more comfortable flight for

them. Second, the night view of Manhattan is absolutely

spectacular, much more so than during the day. Third, and this

is my most important reason, there is very little traffic over the

Hudson at night and, what traffic there is, is very visible.

The Hudson is crowded with planes and helicopters during the day, but

there are few at night.